- Suggested

— 404 Not Found

192 results found (0.003 seconds)

The expression ‘Natural Law’ is used in three related ways: First, in philosophy of law to refer to the idea that as well as the realm of laws made by legislators (‘positive law’) there is another realm prior to and independent of it by which the justice of positive laws may be judged, this being the natural law or ‘natural justice’. Second, as referring to that part of morality that can be known by natural reason in contrast to that which is only known through revelation, hence: natural vs revealed law. Third, in reference to an approach, and to of set of values and principles advocated by that approach, that are rooted in an account of human nature. Versions of all three are to be found in Plato. An example of this third use is the attempt to establish fair principles of ownership and exchange, of marriage and sexual ethics, etc., based on theories of human nature and of what protects and promotes the human good. Critics of natural law sometimes accuse it of committing the ‘naturalistic fallacy’ by trying to derive ‘ought’ from ‘is’. Defenders hold that the criticism is misconceived in assuming an absolute distinction between facts and values, whereas these are often inextricably linked, thus to say that something is cruel is both to describe and evaluate it.

— 404 Not Found

— Revelation shines at least five different kinds of light on . . . .

— Natural Law and Ethical Pluralism was published in The Many and the One on page 89.

— Saint Thomas Aquinas is an Aristotelian (few scholars would question that) and he is the most important author in the entire history of natural law theory. Yet, there is no natural law theory in Aristotle. Even the concept of person, which is so important in Aquinas' ethics, seems to be foreign to Aristotle's culture and thought. How can Aquinas' ethics be said Aristotelian? How can his natural law theory? In From Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas: Natural Law, Practical Knowledge, and the Person, Fulvio Di Blasi argues that Aquinas' concept of natural law, his personalism and his overall approach to moral theory are deeply rooted in the very heart of Aristotle's ethics: in his concepts of practical knowledge, proairesis (moral choice), and practical syllogism, as well as in his account of the moral agency, the ultimate end and human social nature. Di Blasi goes as far as to connect Aquinas' definition of natural law to Aristotle's concept of proairesis. From Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas develops a line of thought that was already sketched in Di Blasi's previous book, God and the Natural Law. Di Blasi engages several authors and critics, including John Finnis, Martin Rhonheimer, Germain Grisez, and Robert George. The first part of the book relates to metaphysics, the concept of good and the concept of practical knowledge. The second part addresses issues in moral philosophy like the concepts of person, the ultimate end, marriage and contraception. The third part applies Aquinas' concepts of natural law, friendship and the person to issues in political philosophy. Di Blasi outlines an ideal of political personalism and the need to recover the concepts of nature and authority in the contemporary political debate. Every student of Aristotle's ethics and politics, and of Aquinas' thought will find this book extremely revealing and stimulating.

— Dr. George’s lecture will explore the various ways that natural law theories lend themselves to our understanding of human dignity, human rights, personhood, and the moral life. He will examine the relationship of natural law to alternative moral theories. This will include an explanation of how natural law relates to theories based variously on commands, rules, obligations, duties, and utility, among others. And, drawing upon the rich Catholic natural law tradition, Dr. George will explain how (or whether) natural law lends itself to virtue-based moral reasoning, accounting for whether law and virtue should be understood as complementary or adversarial.

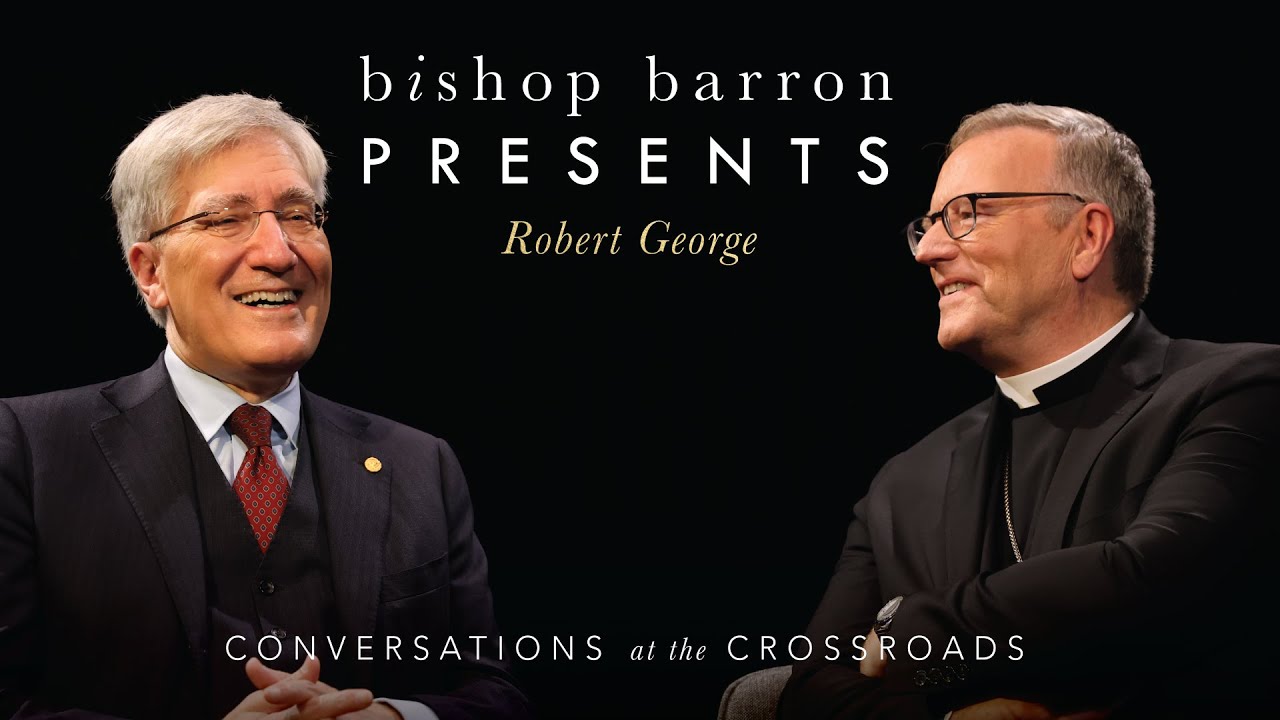

— Friends, it is my pleasure to share the latest “Bishop Barron Presents” discussion, featuring American legal scholar, political philosopher, and public intellectual Robert George. In our conversation, we discuss virtue, focusing on topics such as: - Natural law - The “woke” phenomena - How we can engrain virtue in our society today - And more Stay tuned for future “Bishop Barron Presents” conversations. These intellectually invigorating discussions feature varying religious and political perspectives to encourage greater understanding and civility. ———WATCH——— Subscribe to this Channel: https://bit.ly/31LV1sn Word on Fire Institute Channel: https://bit.ly/2voBZMD Word on Fire en Español Channel: https://bit.ly/2uFowjl ———WORD ON FIRE——— Word on Fire: https://www.wordonfire.org/ FREE Daily Gospel Reflections (English or Español): https://dailycatholicgospel.com/ ———SOCIAL MEDIA——— Bishop Barron Instagram: https://bit.ly/2Sn2XgD Bishop Barron Facebook: https://bit.ly/2Sltef5 Bishop Barron Twitter: https://bit.ly/2Hkz6yQ Word on Fire Instagram: https://bit.ly/39sGNyZ Word on Fire Facebook: https://bit.ly/2HmpPpW Word on Fire Twitter: https://bit.ly/2UKO49h Word on Fire en Español Instagram: https://bit.ly/38mqofD Word on Fire en Español Facebook: https://bit.ly/2SlthaL Word on Fire en Español Twitter: https://bit.ly/38n3VPt ———SUPPORT WORD ON FIRE——— Donate: https://www.wordonfire.org/donate/ Word on Fire Store: https://store.wordonfire.org/ Pray: https://bit.ly/2vqU7Ft

— Article Catholicism and the Natural Law: A Response to Four Misunderstandings religions Francis J. Beckwith Citation: Beckwith, Francis J.. 2021. Catholicism and the Natural Law: A Response to Four Misunderstandings. Religions 12: 379. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/rel12060379 check for updates Academic Editors: J. Caleb Clanton and Kraig Martin Received: 27 April 2021 Accepted: 19 May 2021 Published: 24 May 2021 CC Publisher's Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affil- iations. 4.0/). BY Copyright: 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attrib tion (CC BY) license (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ Department of Philosophy, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76710, USA; [email protected] MDPI Abstract: This article responds to four criticisms of the Catholic view of natural law: (1) it commits the naturalistic fallacy, (2) it makes divine revelation unnecessary, (3) it implausibly claims to establish a shared universal set of moral beliefs, and (4) it disregards the noetic effects of sin. Relying largely on the Church's most important theologian on the natural law, St. Thomas Aquinas, the author argues that each criticism rests on a misunderstanding of the Catholic view. To accomplish this end, the author first introduces the reader to the natural law by way of an illustration he calls the "the ten (bogus) rules." He then presents Aquinas' primary precepts of the natural law and shows how our rejection of the ten bogus rules ultimately relies on these precepts (and inferences from them). In the second half of the article, he responds directly to each of the four criticisms. Keywords: Catholicism; natural law theory; Aquinas; naturalistic fallacy The purpose of this article is to respond to several misunderstandings of the Catholic view of the natural law. I begin with a brief account of the natural law, relying primarily on the work of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's most important theologian on this subject. I then move on and offer replies to four criticisms of the natural law that I argue rest on misunderstandings: (1) the natural law commits so-called "naturalistic fallacy," (2) the natural law makes Scripture superfluous, (3) the natural law mistakenly claims that there is a universally shared body of moral beliefs, and (4) the natural law ignores the noetic effects of sin. My replies are not intended to be exhaustive, but merely suggestive of how a Catholic natural law advocate can respond to these criticisms. Moreover, I do not explore the differing schools of thought embraced by those who identify as natural law theorists. However, attentive readers will quickly recognize the view I am presenting as aligning most closely with what is sometimes called the “old natural law," a view whose advocates defend the idea that, for natural law to work, it requires something like an Aristotelean-Thomistic metaphysics. 1. The Natural Law According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2000, 1956), "The natural law, present in the heart of each man and established by reason, is universal in its precepts and its authority extends to all men. It expresses the dignity of the person and determines the basis for his fundamental rights and duties." This means that morality is real, that it is natural and not a mere human artifice or construction, that all human beings can know it when we exercise our reason, and that it is the measure by which we judge how we should treat others as well as ourselves. This is the moral law to which Martin Luther King, Jr. was referring in his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail (King 1963): “A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law." For King, we can assess the goodness or badness of ordinary human law-whether criminal or civil-by testing it against a natural moral law that we did not invent. Although this way of conceptualizing our understanding of law is rarely verbalized in common conversation, our moral reflexes almost always indicate that Religions 2021, 12, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060379 https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religions 2021, 12, 379 we presuppose it. Think, for example, of how you would react if any one of the following rules were embedded in the laws of your own government:¹ 1. 2. 3. ܩ ܩܙ ܝ 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 2 of 10 Parents may abandon their minor children without any justification and without any requirement to provide financial support. It is permissible for a city or state to pass post facto laws. The maximum punishment for first-degree murder is an all-expense paid vacation to Las Vegas. Any city or state may pass secret laws that the public cannot know. Anyone may be convicted of a crime based on the results of a coin toss. All citizens are forbidden from believing, propagating, or publicly defending the view that there is a moral law against which nations and individuals are measured. Your guilt or innocence in a criminal trial depends entirely on your race and not on a judge or jury's deliberation on legitimately obtained evidence. Government contracts are to be distributed based on family connections and bribes and not on the quality of the bids. Original parenthood is to be decided by a special board of experts appointed by the governor and not on whether one sires or begets the child. No citizen may believe, propagate, or publicly defend the view that there is a tran- scendent source of being that has underived existence. When you reject these ten (bogus) rules (as you should), you do so on the basis of something you already know. You reject rules 1 and 9 because you know that parents have a natural obligation to care for their offspring and that original parenthood is determined by siring and begetting. This is why adoptive parenthood without the explicit permission of the child's natural parents is just a species of kidnapping.² You reject rules 2 and 5 because you know that law should be based on reason. It is unreasonable to prosecute someone for a crime that was not a crime when she committed it, and it is unjust for a court to determine a verdict by an arbitrary and capricious method. Along similar lines, you reject rules 4 and 7. An unknowable law is like a post facto law, and one's race is as relevant to one's criminal guilt or innocence as is a coin flip. You reject 8 because you know that it is unjust for a government to award someone a contract based on their genealogy and willingness to bribe, for neither has any bearing on whether one deserves the contract. You reject rule 3 because you know that human life is sacred and that a just society must reflect that in its laws. To reward someone for intentionally killing the innocent is an abomination. Because you know that the human mind has a natural inclination to know not only particular and mundane truths, but universal and transcendent truths as well, you reject rule 10. For rule 10 essentially prohibits the full exercise of a power that is distinctly human, what Aquinas called "speculative reason." "³ And finally, you reject rule 6 because you know that societies and individuals can be properly judged by a moral law external to their own practices and beliefs. You know on a personal level that you sometimes fall short of the moral law's requirements. Like all of us, you make excuses, rationalize, or ignore your own moral indiscretions, though on occasion you are moved by conscience to confess your wrongdoing. But what is true of individuals is also true of civilizations, for it seems perfectly permissible for one to issue judgments about the conduct of nations that have perpetuated atrocities and injustices, even when those nations' apologists rattle off a litany of excuses and rationalizations or feign ignorance. According to the Catholic Church, your rejection of the ten bogus rules is the result of your acquaintance with the natural law, even if you are not conspicuously aware of it. This is possible because human beings are ordered toward certain goods, and as rational animals, we have the capacity to recognize and make judgments about those goods and realize that we ought to choose them. As Aquinas notes, “Since .. good has the nature of an end, and evil, the nature of a contrary, hence it is that all those things to which man has a natural inclination, are naturally apprehended by reason as being good, and consequently as objects of pursuit, and their contraries as evil, and objects of avoidance." (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 2, respondeo). What Aquinas is saying here is that we are, in Religions 2021, 12, 379 3 of 10 a sense, hardwired to acquire knowledge of the precepts of the natural moral law, just as we are hardwired to learn mathematics and speak a language and discover rules about them.5 To understand what Aquinas means, we will review his brief account of what are sometimes called the primary precepts of the natural law. It is from these primary precepts, Aquinas argues, that we can derive other precepts, which he calls the secondary precepts of the natural law (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 5, 6). (1) "[G]ood is to be done and pursued, and evil is to be avoided." (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 2, respondeo). Calling this the first precept of the natural law, Aquinas grounds it in the common-sense observation that every human being knows at some level that she ought to seek after what she believes is good for her, even if it is not really good for her. The alcoholic, for example, pursues the bottle because he desires the good of being at rest, to attain some sense of internal peace and contentment. When he conquers his addiction and changes his ways, he does so because he more fully understands how best to fulfill this first precept. He realizes that by his excessive drinking he had unwittingly been violating the precept, that he in fact was not really doing good or avoiding evil. Although you reject each of the ten bogus rules for specific reasons, e.g., the precept that one ought not to intentionally kill the innocent, your duty to act in accordance with those reasons depends on this more general precept: good should be done and evil avoided. (2) "[W]hatever is a means of preserving human life, and of warding off its obstacles, belongs to the natural law.” (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 2, respondeo). Like all living things, human beings have an inclination to continue in existence. But unlike those other living things which are directed by mere instinct or learned behavior, and not by intellect and will-human beings can apprehend the sort of existence appropriate to the kind of being we are. So, when Aquinas talks about "preserving human life”, he does not mean mere biological existence. We do, of course, apprehend the evil of killing, since we apprehend what is good for us. But we also know that the preservation of human life consists in far more than mere survival, but must include the sorts of relationships, institutions, and communal goods that make life worth living and allow us to flourish consistent with the ends of our nature. Although we rightly conclude from this precept that we ought to avoid death and not kill, we also come to recognize, by the exercise of our reason, that preserving the life appropriate to our species entails that killing may sometimes be justified and death should not be avoided at all costs. Thus, we come to believe that there are cases of permissible killing, e.g., just war, self-defense, as well as cases in which not avoiding death is not a violation of the natural law, e.g., martyrdom, certain supererogatory acts. The justification of those apparent exceptions is the result of a further elaboration of the natural law. Take, for example, self-defense. Because I have an inclination to preserve my life, I have a right to protect it, which means that there may be occasions in which my exercise of that right results in the death of the assailant trying to unjustly take my life. As we shall see in the fourth primary precept, because we are rational and social beings that are ordered toward the shunning of ignorance, knowing the truth about God, and living with others in peace, we can infer from the natural law's primary precepts more precise precepts about the extent to which we are permitted to kill (“You may kill in self-defense so that your life may not be unjustly taken by someone who does not want to live at peace with others") or not avoid death ("Your duty to God, which is your highest duty, may require that you die for your faith if denying it is the only way to avoid death.") Hence, your rejection of bogus rule 3 is based on a secondary precept of the natural law: one should not intentionally kill the innocent. (3) "[T]here is in man an inclination to things that pertain to him more specially, according to that nature which he has in common with other animals: and in virtue of this inclination, those things are said to belong to the natural law, 'which nature has taught to all animals' , such as sexual intercourse, education of offspring and so forth.” (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 2, respondeo). Here, Aquinas is telling us that our sexual powers are ordered toward reproduction and that we have a solemn responsibility to our offspring .../ Religions 2021, 12, 379 4 of 10 that are brought into being from the exercise of those powers. Like all animals, we have a natural inclination to reproduce and care for our young. But unlike other animals, we possess intellect and will, which means that we can choose to resist our natural inclinations while still apprehending why it is sometimes evil to do so. For this reason, we infer from this primary precept of the natural law that child abandonment and state denial of parental rights are both prima facie evil. As should be obvious, your knowledge of this secondary precept of the natural law is the reason why you reject bogus rules 1 and 9. (4) "[T]here is in man an inclination to good, according to the nature of his reason, which nature is proper to him: thus man has a natural inclination to know the truth about God, and to live in society: and in this respect, whatever pertains to this inclination belongs to the natural law; for instance, to shun ignorance, to avoid offending those among whom one has to live, and other such things regarding the above inclination." (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II, Q94, art. 2, respondeo). Here, Aquinas is saying that we have an inclination to reason well and eschew ignorance (because we are beings with intellect), live peaceably with others (because we are socially dependent beings), and know the highest truth (because we are beings with intellect that may exercise speculative reason). That is, we are naturally ordered toward these ends and to intentionally act contrary to them is to engage in evil. It is clear from your rejection of bogus rules 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 10 that you already know this. Bogus rules 2 and 4 intentionally make citizens ignorant of the law, bogus rules 5, 7, and 8 enshrine irrationality in the law, and bogus rules 6 and 10 prohibit citizens from pursuing and expressing the highest truths about morality and God. Also, all the bogus rules in one way or another make it extraordinarily difficult to avoid "offending those among whom one has to live." For Aquinas and the Catholic Church, natural law is not the only kind of law. There is eternal law, divine law, and human law, all of which are essential to understanding the natural law. Eternal law is the order of the universe in the mind of God. Divine law is Sacred Scripture. And human law is the civil law and law of nations instituted by human governments. I will have more to say about each in Section 2, since some of the misunderstandings to which I will respond are often the result of natural law's critics ignoring one or more of these other types of law. 2. Four Misunderstandings In this section, I am going to assess four misunderstandings of the natural law. I intend nothing more than to offer corrections to how some critics of the natural law conceptualize it. Thus, my comments are not meant as a defense of the truth of the natural law (though I believe it is true) but, rather, as a clarification of what the Catholic Church (and Aquinas) actually believes about the natural law. Because the second, third, and fourth misunderstandings are clustered together in a famous article by the Evangelical theologian, Carl F. H. Henry (1995), I address them together under one heading. 2.1. The Natural Law Commits the So-Called "Naturalistic Fallacy" Some critics of the natural law argue that it commits what is sometimes called the "naturalistic fallacy," that its advocates mistakenly try to derive an "ought" from an “is,” a normative conclusion from a factual premise. So, for example, it would be fallacious for one to argue from the fact that peyote is a naturally growing substance to the conclusion that one ought to consume peyote. In the same way, points out the critic, the natural law theorist fallaciously argues from the facts of human inclinations to the conclusion that one ought not to intentionally act contrary to them. Although it is certainly true that it is sometimes fallacious to attempt to derive a normative conclusion from a factual premise—e.g., pot smoking is legal therefore you ought to smoke pot-this is not always the case. For one thing, the “facts" with which the natural law theorist is working are embedded in a teleological worldview, one in which all living creatures have natures that tell us what is good for them as well as inclinations that move these creatures to those good ends. The sapling in your back yard, for example, is Religions 2021, 12, 379 5 of 10 ordered toward becoming an oak tree and thus it has inclinations to perform photosynthesis and absorb minerals from the soil for that end. Because we know the sapling's nature, we know that its becoming an oak tree is a perfection of its nature and thus good for it do so. But, as I have already noted, human beings are not like other creatures, for we have intellect and will and are thus able to make real choices that may be contrary to or consistent with the good to which our inclinations are ordered. So, for example, if one is purposely ignorant, abandons one's children, or intentionally kills an innocent bystander, then one has made an immoral choice contrary to the goods to which one is ordered, which includes the acquisition of knowledge, the caring for one's offspring, the preserving of human life, and living at peace with others. To be sure, some philosophers reject natural teleology altogether, along with the Aristotelean-Thomistic metaphysics on which its advocates typically rely, while others, the so-called "new natural law theorists," believe that the truth of natural law does not depend on natural teleology (see Lee 2019; Crowe 2017). But given the modesty of our task-to merely offer conceptual clarification on how the Catholic Church, and how Aquinas (as conventionally interpreted), understands the natural law¹0_there is no need to wade into those extra- and intramural disputes in this venue. Second, outside of explicit discussions of natural law, we often make legitimate judgments that seem to rely on natural facts that imply good ends that one ought to pursue. Consider first the comments made by Richard Dawkins about Kurt Wise, a Harvard-trained paleontologist. Wise was brought up in a Fundamentalist Christian home in which he was taught that the Bible teaches that the Earth is no more than 10,000 years old. Not only did Wise not abandon this belief after earning his Harvard PhD, but he came to the conclusion that if he were to do so, he would be abandoning his faith in Scripture, the Word of God. So, by sticking with his young earth views, Wise recognized that he had given up any chance of landing a professorship at a major research university. In an autobiographical essay quoted by Dawkins, Wise laments: “With that, in great sorrow, I tossed into the fire all my dreams and hopes in science." (Ashton 2000; quoted in Dawkins 2006, p. 285). In his assessment of Wise's decision, Dawkins writes: 11 As a scientist, I am hostile to fundamentalist religion because it actively debauches the scientific enterprise. It teaches us not to change our minds, and not to want to know exciting things that are available to be known. It subverts science and saps the intellect. The saddest example I know is that of the American geologist Kurt Wise ... The wound, to his career and his life's happiness, was self-inflicted, so unnecessary, so easy to escape. All he had to do was toss out the bible. Or interpret it symbolically, or allegorically, as the theologians do. Instead, he did the fundamentalist thing and tossed out science, evidence and reason, along with all his dreams and hopes. (Dawkins 2006, pp. 284, 285) Note the teleological reasoning undergirding Dawkins' assessment of Wise. He is saying that Wise—an intelligent, gifted, and well-credentialed scientist-ought to have used his talents in a way that would have led to his happiness, and that his fundamentalist beliefs were an impediment to that end. Because of the sort of being Wise is―a being with intellect and will whose end is happiness—he has an obligation to make choices consistent with that end. Aquinas, unsurprisingly, concurs: "[M]an's last end is happiness; which all men desire, as Augustine says (De Trin. xiii, 3,4)” (Thomas Aquinas 1920, I.II Q1.art8, sed contra). 12 Now consider the fanciful case of David and his optometrist, Thomas. Suppose David is examined by Thomas, who tells him,¹3 "It looks like you are nearsighted and you ought to use corrective lenses." David replies: "But doc, you just made an illicit inference, for you can't get an ought from an is. Just because I am nearsighted doesn't mean that I ought to use corrective lenses. At least that's what Hume taught me.' ."14 Thomas, having read Aquinas, responds with a series of questions to which David offers a series of replies: "Should you do good and avoid evil?” “Yes.” “Is improved eyesight good for you?” “Yes.” “Would corrective lenses improve your eyesight?” “Yes." "So if you should do good and avoid evil,

— *NOTE: The intro to this recording was lost. This video begins a few minutes into Gregg's lecture.* Dr. Samuel Gregg is the research director at the Acton Institute. He has written and spoken extensively on questions of political economy, economic history, ethics in finance, and natural law theory. He has an MA from the University of Melbourne, and a Doctor of Philosophy degree in moral philosophy and political economy from the University of Oxford. He is the author of thirteen books, including his prize-winning The Commercial Society (2007), For God and Profit: How Banking and Finance Can Serve the Common Good (2016), and Reason, Faith, and the Struggle for Western Civilization (2019). He has also co-edited books such as Natural Law, Economics, and the Common Good (2012). Two of his books have been short-listed for Conservative Book of the Year.

— This book provides the first systematic, book-length defence of natural law ideas in ethics, politics and jurisprudence since John Finnis's influential Natural Law and Natural Rights. Incorporating insights from recent work in ethical, legal and social theory, it presents a robust and original account of the natural law tradition, challenging common perceptions of natural law as a set of timeless standards imposed on humans from above. Natural law, Jonathan Crowe argues, is objective and normative, but nonetheless historically extended, socially embodied and dependent on contingent facts about human nature. It reflects the ongoing human quest to work out how best to live flourishing lives, given the natures we have and the social environments we inhabit. The nature and purpose of law can only be adequately understood within this wider context of value. Timely, wide-ranging and clearly written, this volume will appeal to those working in law, philosophy and religious studies.